ABOMINABLE SIN

Part 1

The Apple Wagon

Rachel squinted her eyes against the glare of the sun to see the lone rider beyond the gate where husband Henry stood, his arms gesturing widely, both men deep in conversation. With the visitor’s face half stripped from view by shadows, she did not fully recognize him. In the intervening distance between the clothesline, sagging with dripping clothes and bed sheets, and the wooden gate, she thought him to be Elder Isaiah. Immediately apprehensive, she felt a quickening of her heart. Lone riders coming through their gate meant messages, godly commands that could not be ignored.

Why now? Why in the throes of the Eleventh Month?

She grimaced, hoping the rider was not Elder Isaiah. Couldn’t be a shipment. Shipments were out of season just as fresh peas from the garden were months away. Throwing the last of the overalls over the frayed rope clothesline, she straightened her back, her brows gathered, to verify the half-hidden face was that of the Elder. She sloshed the wash bucket, turned it upside down to drain, and slowly approached the gate. Before she reached Henry, the rider tipped his black, broad-brimmed hat, cropped his horse, and sped away in the direction of the meeting house, an unadorned structure standing on the next hill among old burned stumps dotting a narrow clearing.

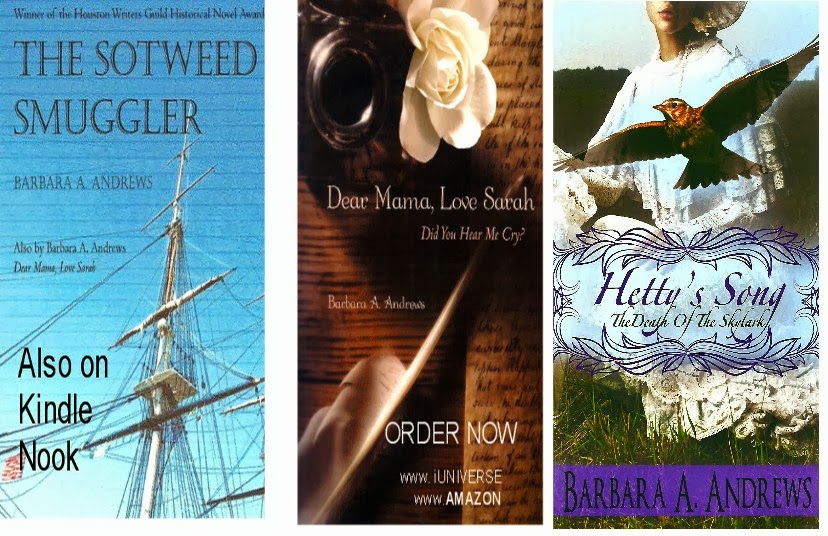

Farmers Greenfield Academy

Photo by Bobi Andrews

Henry called after the departing rider, “God be with thee.”

“Pray, was that who I fear he was?” Rachel asked, an edge of irritation in her voice. She resented Henry being so secretive that she must ask before he would share what she had a right to know. Widowed with three children before submitting to the Meeting’s demand she remarry, she now was pregnant with Henry’s child.

“’Twas Elder Isaiah. Shipment’s coming. Left Vincennes yesterday, arrived in Terre Haute today. Will be in Crawfordville next.”

Henry, a committed Friend, but a demanding and ill-tempered Dutchman, turned his gaze abruptly to Rachel with more than a hint of sarcasm in his voice, “Isaiah says it’s thy turn.”

Anxiety crossed Rachel’s brow. She suppressed words she would like to have uttered and listened to Henry only long enough to ask, “By night or by day?”

“Been by night as far as Terre Haute. Followed the Wabash. Thy leg will be in daylight. No cover. Brush and trees along the Flint are frozen bare and no high banks to hide under. Have to move by wagon on the road.”

Trees by Flint Creek

Photo by Bobi Andrews

Rachel swallowed hard. “’Tis too late in the year for a shipment, is it not?”

“Woman,” he snapped, “Thou knowst God’s will must be done.” His was the voice of zealot obedience, not of a compassionate heart.

“But Husband, I cannot go and thou cannot take my place.” She frowned her dismay, recognizing the transport was beyond her will to change. “Thou narrowly escaped the last time. In daylight, thou will be recognized and all will be lost.”

“Wouldn’t go anyway. Corn’s rotting in the field. I cannot spare a day.”

She rubbed the roundness of her stomach, her lips parting tentatively as if she might change her mind and go. Instead, she shrugged hopelessly. “It’s too late in my term, I cannot go. What will we do?”

He didn’t respond right away, then answered, his word alone settling the issue. “Thou must send thy daughter.”

“Thou cannot be serious. She is but thirteen.”

“She’s no child. Old enough to wed,” he grunted. “Thy daughter is stout and strong as a well rope. She’s driven field wagons before, this will be no different. No one will suspect her.”

Rachel flashed her eyes in disagreement not believing his words, her passion escaping like molten ash from her tongue. “Do not make me send her.”

In a tone impossible to please, he commanded, “Thou has no choice. It’s God’s journey. Crawfordville is south of here. Slave hunters know runaways don’t travel south. Nothing will happen.”

“If thou promises she shan’t fall into harm . . ..” Her voice tapered off. She turned, calling to the house, “Sarah Ann.”

-----

I heard my name. Moments before, while collecting eggs, I had seen through the grimy frosted window of the chicken house the visitor’s horse disappearing into the trees and sensed something of importance was about to happen.

To listen to everything Father Henry said to Mother, I dashed to my hiding place, crouching behind a fallen sycamore tree, which was dead beyond redemption and had splintered the rail of the house fence.

I knew of what they spoke. When Papa was alive, he and Mother, like Brothers and Sisters of faith, abhorred slavery . . . mankind’s abominable sin. Papa’s deep, mellow voice echoed in my head. “No man shall own another man. It’s God’s will to deliver to freedom those in bondage.” In our house, taking turns in the spring and summer hiding shipments from the tree-lined creek and traveling north to Canada was as common as cornbread mush and buttermilk at supper. We thought the secret cellar under our barn and the slanted vacant spaces between walls in our closets nothing unusual.

We knew the danger and the secret codes. When we were little, my brothers and I pretended to be slaves crawling from the creek in the middle of the night to the hiding place in the barn’s cellar. We knew when Papa expected a gathering from Flint Creek. Told to be absolutely quiet, we hurried to bed, stumbling without candles, with heavy curtains drawn tight across the windows.

-----

At Mother’s call, I ran from behind the sycamore tree. “I want to go,” I begged. “I’m the oldest. Others my age go. Papa said he drove his first wagon when he was eight.”

“But Sarah Ann, not unmarried girls and not alone. God forbid,” Mother argued, her quivering voice thin, her eyes narrowing. “Ungodly men are on the road and thou could not protect thyself. They are not like thy father.”

“If brother Cephas goes, I won’t be alone. He’ll ride in back while I drive. He’s practiced the signals, hoots like a real owl, and won’t be afraid. Elder Isaiah left his wagon in our barn after the last delivery knowing we’re next. We know about the boards in the bed of the wagon and how the box works.”

“A mere girl traveling with a ten-year-old boy?” She wrung her hands, her eyes distraught and uncertain. She turned to Father Henry. “I don’t know, Henry, there is so much danger. I don’t believe for a moment men hunting runaways have left us.”

Father Henry’s sharp frown and hard-set eyes forbade further argument. He pointed to Mother. “Shipment originated from thy people on the Ohio and got this far along the Wabash sheltered by thy Vincennes brother. Thy brother in Crawfordville will make the transfer. All thy daughter has to do is find his barn. He ought to be willing to have one of his sons ride back with her.”

Mother shook her head slowly, showing disgust that he spoke harshly, not in fellowship of faith and love. I saw the hard look she gave him, but without further word, she turned her steps back to the porch where the wash tub remained. Following the secret code didn’t require a second thought for any of us. From the bench Mother took the faded safe-house quilt—the one stitched with a cabin and smoking chimney—and reluctantly hung it next to her wash on the clothesline. Finishing the code, she overturned a nearby kettle.

Elder Isaiah would now know arrangements were complete.

-----

“Is this necessary?” I asked. Although the sun had been up for an hour, silvery streaks of frost clung to the top of the barn where I had sent Cephas to hitch the Elder’s wagon, loaded with apples, to a pair of mules. “Really, Mother, isn’t it more important Cephas and I get an early start?”

“Everything is important. Thou hast to look older. Brush up thy hair so my bonnet will cover. A little ash dust will gray thy hair and make thy face older. My dress will cover thy ankles and legs, and these rags in thy bosom will lower thy breasts. Whatever happens, don’t let thyself be taken from the wagon.”

I saw Mother force a smile that aged her by sending wrinkles of worry up her cheeks and around her eyes. From the tone of her voice, I knew she wasn’t finished with her warnings.

“If a slave hunter asks where thou is going, what is thy answer?”

“Mother, we’ve practiced this over and over already. I’ll say, I’m taking the apples to my uncle to sell in Crawfordville.”

Mother persisted. “And where is thy husband?”

“I have no husband. My father’s dead, died last year. The boy is my brother.”

“And thou knowst how to get to Uncle John’s barn?”

“Aye, and don’t tell me, Mother, I know not to let anyone follow me there.”

“And what will thou do if followed?”

“Go to the Crawfordville meeting house and wait until it’s safe.”

Tears formed in Mother’s eyes. She touched my shoulder, the back of her hand gnarled beneath reddened, chapped skin. “Oh, Sarah Ann, I don’t know if I can let thee go.”

“Mother, just pray. Cephas and I will be fine.”

“Time to go,” I called to Cephas standing near the loaded wagon. “Tie Rolfe to the tree.”

“Nay, I’m bringing him. He’s a good tracker and guard dog. He’ll ride in back with me.” I suspected he wanted to take advantage of Rolfe’s thick fur to keep him warm.

I pointed to the bottom box of the wagon. “What if he barks on our way home when we have the shipment with us?”

“He won’t bark. I trained him to stay quiet when I tell him to ‘stay.’ We’d better leave before Father Henry notices him missing.”

Cephas jumped on the tailgate hugging Rolfe next to him. In all honesty, I thought a dog would help more than ashes in my hair.

“Is thou settled and the apples piled to cover the bottom?”

Cephas crawled to the back board behind me. “Aye, sister.”

“Then we’re off.” I wrapped my scarf over my mouth to buffer the wind and entered the road thinking the trip would be a good time for Cephas and me to be alone away from Father Henry’s continual complaints.

Cephas read my mind. “Thank thee, Sister, for asking that I come along. If I weren’t here with thee, I’d be slopping hogs and cutting cornstalks.”

“Me, too,” I grinned. “Keep a keen eye, and pray nothing happens before we get back home.”

A two-pony wooden truss appeared ahead to provide passage across Flint Creek. Below the structure, small areas of cleared banks allowed for fishing. Beyond was a wedge of trees, tangled and overgrown with dried vines, their leafless skeletons darkening the sunlight. “It’s when we get into those trees that it gets scary.” I cautioned, “Watch out. Anything and anyone could hide in there.”

“I used to get scared when Papa took us to Uncle John’s.” For a boy of ten, Cephas had a good memory and an equally good imagination. “Once we’re in the trees it’s like being swallowed by a big grizzly bear—no way out.”

I tried not to imagine the picture he was describing. Instead, I stared at a distant oak tree wondering whether I saw a blackbird or a large dead leaf outlined on one of the branches. The leaf lifted its wings and flew away leaving me with the truth: bears haunted these woods along with screeching bobcats and howling wolves. Shuddering, I pulled my cape closer to my chest and glanced both ways.

At the edge of the trees, an empty hay wagon emerged with two Friends from the Meeting wearing tall, round brim hats which matched their long black beards. They waved, “Halloo, Sister.” I pulled our wagon closer to the edge of the road to let them pass. Rolfe barked as their wagon rolled on.

My nerves settled, and I flicked the reins to spur the mules. I put the grizzly bear nonsense behind me but resolved to get through the woods as fast as I could. I turned to talk with Cephas when suddenly my courage bled away like a hog hung from a hook. I felt my face drain to a ghostly white. But it wasn’t ghosts ahead. Two men blocked the wagon path, rifles in hand, their appearance filthy as if they lived permanently on their horses. Dark creased hats with pheasant feathers in the bands covered their straggly hair, and tucked-in, ragged trousers topped soiled boots. One spat to the ground while the other’s eyes darted from side to side finally resting a licentious gaze on me.

I swallowed hard and looked for an opening in the woods, but like Cephas’s fearsome imagination, there was no escape. Thankfully, they had not seen him.

I whispered over my shoulder, “Cephas, stay under the seat. Don’t say a word.”

The taller of the men advanced, forcing me to halt. With a dry laugh and a guttural sound emerging from his throat, he demanded, “Whoa, what do we have here? One of those quaking cowards?” His mouth turned to a sneer. “Where you going, Sweetheart?”

I resented his attitude. We were the Society of Friends, not quaking heathens. With Mother’s voice ringing in my ear, I summoned courage. “To my Uncle’s with our apples.”

“Apples? You wouldn’t be hauling anything else would you?”

I met his accusing gaze and answered firmly, “Nay, only harvest apples.”

He held my eyes, my fears growing as his eyes narrowed, showing his suspicion. “And where might this uncle live?”

“Crawfordville,” I answered, then regretted giving him that information.

The two men rode slowly around my wagon stopping abruptly when they spied Cephas sunk down in the apples next to the back board behind me. The taller man raised his whip. “If you know what’s good for you, Boy, you’ll show yourself.”

“Please, he’s my little brother. Don’t hurt him.”

“Now that depends, Sweetheart, on how friendly you are, don’t it, Otis?”

“That’s right, Jeb.” He rubbed his chin with anticipation. “You first.”

Jeb dismounted with a cocky smile, reached for the side of the wagon, and thrust his hand over the top to grab Cephas by the coat.

A fierce growl erupted and a mouthful of sharp teeth seized the man’s sleeve, drawing a gush of bright red blood from deep in his arm.

“What the Sam Hill? Get the damn dog off me,” he shouted. “Otis, hand me my rifle. This dog’s dead meat.”

Cephas’s quivering voice whispered, “Stay, Rolfe, stay.” He pulled Rolfe against his shoulder, hugging his neck to protect him. Rolfe growled viciously.

I screamed. A flock of alarmed birds burst from a tree. “We aren’t armed. Let us go.”

With the sound of hooves echoing at a distance, I saw dust filtering through the trees ahead. Minutes later, the noise of galloping horses grew louder although we saw nothing on the road. In unison, Cephas and I yelled, “Help!”

Jeb put the rifle between his knees and cocked it with his good arm. He aimed at Rolfe. Startled by our outcry, he paused a moment before firing. From around the bend, three horsemen raced, hollered, and fired rifles. Otis grabbed Jeb and pulled him onto his waiting horse. Racing past my wagon, they fled in the opposite direction from the approaching horsemen.

Three riders halted. The lead rider dismounted, his gray gentlemen’s coat frayed, but presentable.

“Ya’all hurt?” he inquired, his voice a friendly drawl.

“Nay,” I said. I took a deep breath and steadied my voice. “Bandits.”

My relief was short lived. His next question set my heart pounding. “You see any runaways around here?”

A new fear streaked straight through my body, head to toe. A lump in my throat grew, choking me like a rope tightening about my neck. I barely managed my response. “Nay, no runaways. Brother and I are on our way to Crawfordville to my uncle’s to sell apples. Haven’t seen anyone but the two bandits ye chased away.”

He held me in his gaze for a minute and suggested gently, “Mind if I ride with you to Crawfordville? Ain’t safe for a lady and a boy alone. Going that direction anyway. You could run into more bandits.”

I hoped he didn’t feel my reluctance when I nodded my assent. Saved from bandits by a southern gentleman. But a slave hunter? I had to keep my wits and figure a way to get rid of him before Crawfordville. The meeting house was at least six miles away, Crawfordville maybe four.

The rider nodded for the other two to proceed on their way, tied his large, dappled gray appaloosa to the wagon, and climbed onto the front board beside me, sitting so close, I felt heat coming from his body. Without looking directly at me, he tipped his hat and announced, “Judson Claymore.”

I bent my body forward and turned my head to let Mother’s bonnet shade my face. I felt perspiration cake the ashes and imagined how hideous I looked. I expected he’d discover the truth any minute. Rolfe snarled.

“Cephas, keep Rolfe quiet. Gentleman means no harm.”

To distract him from focusing on the apples in the wagon and maybe suspecting the false bottom, I struck up a conversation. “And where, Mr. Claymore, might thou be from?”

“Lexington, Kentucky.” He handed me a poster. “Looking for this here Toby and his sister. Ran away two months ago. We tracked them to the Wabash but lost their trail after Vincennes. Suspect some abolitionist has them.” He looked at me slyly, a scowl of annoyance passing over his face. “Maybe your kin, huh?”

“Oh nay, wouldn’t be us. My mother farms corn and wheat and has an orchard for apples.”

“No father?”

“He died. Just my brothers and me besides my mother.”

Claymore removed his hat and placed it over his heart. “Ma’am, my deepest regards for your loss.”

-----

“Thought you said Crawfordville. You missed the turn.”

“Should have said outside Crawfordville. We’re to meet Uncle at the meeting house. His creek usually overflows and he’ll help us get through.” The road widened and Crawfordville lay to the left. Now or never, I thought. I tried to imagine what Mother would say.

“I thank thee for staying with us, but once at the meeting house, we’ll be safe. We wouldn’t want to keep thee from thy search any longer.”

“When I see you safe at the meeting house, I’ll see.” He persisted, “A gentleman never leaves a lady on a road alone.” A small voice warned me. Claymore was a stranger, the kind Mother preached to me about, but with the concern I heard in his voice, I thought him sincere. Strangely, I didn’t fear he would harm Cephas and violate me.

In a few short miles, a desolate meeting house loomed, the windows boarded with shutters against winter blizzards, no smoke rose from the chimney. I knew we were alone and imagined Claymore would soon realize no one expected us. To my relief, he said nothing.

“Cephas, we’re here.” Ignoring the obvious, I called, “See if you can find Uncle John.”

“Not here yet, yard’s empty,” Cephas responded, a knowing tone in his voice.

“We did say sundown. He must be on the road. Gives us time to make our prayers.” I climbed from the wagon and tied the mules to a rusty ring on a post. I swished Mother’s skirt confidently and tossed my head. “Come, Cephas, bring Rolfe.”

We entered the cold, darkened meeting room. Our breaths fogged from our mouths as we rubbed our cold hands together. I found two short candle stubs with flint and tow on a worship table and scraped a light to see beyond the door. I gave one to Cephas and motioned for him to follow me to the front pew where we sat with our heads bowed. I prayed the Lord forgive my falsehoods, and that the slave hunter didn’t know women were forbidden to sit on the men’s side. Claymore stood awkwardly inside the door shifting from one foot to another. He watched us for a minute or two, then turned and left. We heard his horse whinny.

“Sister, what will we do? Candles won’t last. It’ll be dark and we have no lantern. I’m freezing.”

“We’ll stay the night right here and sleep in the pew. Bring wood for the stove while I still have my candle lit, and turn over the kettle on the step. Tie Rolfe by the door to guard us. Thou can’t be that scared.” I turned my challenge into a tease. “Are thee?”

Pews in Farmers Greenfield Academy

Photo by Bobi Andrews

“Not scared, Sister, just hungry.”

“We won’t starve, Cephas.” I tousled his hair and smiled. “We’re safe. The Lord hath provided.”

“Provided what?”

For the first time since leaving home, I relaxed and laughed, “We got apples, a whole wagon of them.”

A sheepish grin crossed Cephas’s face.

-----

The next morning, Uncle John greeted us with a solemn, kindly face, typical of Mother’s brothers. A devout believer in God’s inner light, and stern in manner, he was my favorite of all the uncles.

“I worried for thee, Sarah Ann. Expected thee last night. Was there trouble, now?”

“Aye. Bandits stopped us first and then slave hunters drove them off, but one of them insisted on riding with us. I couldn’t let him follow us here, so we stopped at the meeting house. Started this morning at dawn and saw no sign of him.”

“Is thou all right? I mean, the slaver didn’t . . .” Uncle John paused and groped for words.

I knew what he was asking. “Nay, Justin Claymore didn’t touch either Cephas or me. Seemed only interested in his slaves.”

Cephas slid from the rear of the wagon boasting, “We slept on pews and ate apples. Weren’t scared at all.”

“Brave boy.” Uncle John winked at me. “Thy cousin James spotted the overturned kettle this morning. Hoped it was thee in the area. Far as I know, this shipment is the only one moving in Crawfordville.” He extended his hand to help me lower myself to the ground. “How is my sister? No child, yet?”

“Mother says soon. She’s not pleased I came, but she had no choice.”

“I would agree with thy mother. Dangerous business this is. Shipment is a young buck and his sister. Knows nothing of Indiana and wasn’t taught to read. Won’t make it far on his own. Sister is blind from a beating about her head. Boy said he ran from the plantation to save her. I can load them without ye seeing them, if thou prefer.”

“Nay, I don’t consider God’s mission the same as hauling hogs. Of course, Cephas and I want to see them.”

“Then come along. I’ll send thee back with fire wood in case the same slavers spy thee. Wouldn’t do to return with apples.”

I followed Uncle John to his barn and watched him lift hay from the floor with his hayfork. He took the handle and pried it under a loose board, catching a small door rising from a hidden swivel.

“Dark and damp down there. Barely room to sit. How do they breathe?” I asked.

“That’s why they can’t stay long in any one place. I give them food and move them on just like ye will do.”

He toggled the door on the floor and stretched his hand below. “Hand up thy sister first.”

He pulled on an extended arm. A curly-headed girl of ten emerged, wrapped in a blanket, with vacant eyes and scars etched deep in her forehead. Frightened, she whimpered.

“Don’t cry, Sunshine, I’m behind you,” a voice came from below.

I pulled the girl next to me under the crook of my arm.

“Catch thy foot on the rope while I pull thee up,” Uncle John said to the body climbing from the cellar.

A young boy, desperately acting like a man, braced his hands on the barn floor and pushed himself the rest of the way, shading his forehead to see in the bright light. He lowered his eyes, turned his face toward me, and reached to comfort Sunshine. He was no older than me.

I gasped. I stood face to face with a tall, skinny boy with round eyes, unevenly clipped hair, a scar near his left ear, and thick, protruding lips—the spitting image of the drawing on the poster Judson Claymore showed me yesterday.

Uncle John looked askance. “What’s the matter, Sarah Ann? Something wrong?”

“He’-s-s Toby,” I stuttered, “Claymore’s runaway.” In that instant I knew the difference in danger between an unknown fugitive running, and another, the target of the owner who rode in my wagon yesterday and still lurked in the area. The distance between here and home seemed a thousand miles. I felt helpless.

“Mother wants me to ask thee if James can ride back with us.”

Uncle John rubbed his chin. “With Claymore in the area, that does put a different slant on things. He knows thee, and if he looks hard, he’ll find what he’s looking for. I wouldn’t suspect thee would find him a gentleman the second time.”

“Then James can come back with us?” I heaved an enormous sigh of relief.

“I can’t do it. A cow’s down and James tends her night and day. Can’t afford to lose her calf. I hadn’t planned on sending anyone or I would have taken Rachel’s turn myself.”

“But Uncle John, the slave hunter . . .”

“For now, take these two and have your Aunt Hannah fix them something to eat while I think about it.”

A few minutes later, James and Uncle John entered the kitchen where Aunt Hannah sliced hard bread and added chunks of jerky and dried pumpkin rings to small cloth bags.

James spoke. “Ma, fix me a bag, too. I’m going with Sarah Ann and Cephas until they’ve passed beyond the woods.”

“But no further,” Uncle John scowled. “Thou hast to be back before dark.” He grumbled below his breath. “Henry should be doing this, not us.” Unhappy with the unexpected turn of events, he slammed the kitchen door and motioned for Toby and Sunshine to follow.

Cephas held the traces of the mules with the wagon stopped near the wood pile. At the sight of Toby and Sunshine, Rolfe wagged his tail and gave a friendly bark.

“Cephas, shut that dog up and give me a hand,” Uncle John ordered. “Get on that end and slide the board toward me.”

He scanned Toby’s tall frame, his eyes moving slowly from head to foot. “It will be a tight fit, thou art taller than most and the girl has to squeeze in beside thee.”

“We’ll fit, Suh.” Toby crawled in from the back of the wagon doubling his long legs into the short, narrow space. He called, “Sunshine, ready for you.”

“I’ll help,” Cephas offered. “I know she ain’t seeing where she’s supposed to be.

Sunshine, thy place is beside Toby so thou will be safe.” He put Sunshine’s hand in Toby’s. Fitting like spoons, Toby squeezed his sister in front of him.

I placed two small bags of food in Sunshine’s lap with two rags dripping with water. “Suck on the rags if ye get thirsty.”

James and Uncle John replaced the wagon boards, and with Cephas, quickly loaded the chopped wood. Cephas crawled on top of the pile with Rolfe furiously pawing through the stacked wood.

“That dog’s trouble,” James said. “Get him down from there. Let him run loose.”

“No, James,” I said, “Claymore knows him, too. He’s apt to spot Rolfe roaming before he sees us. Tie him here with me. He’ll sleep under the seat.”

James mounted his horse. “Keep thy pace slow and steady. Sometimes I’ll be ahead of thee, sometimes I’ll follow.”

I snapped the reins and the wagon moved forward.

With James nearby, I looked about as we entered the woods just north of Crawfordville. Somehow, the shadows from the trees didn’t look as frightening. The things that were supposed to be there were—birds, squirrels, and a rabbit that sent Rolfe pulling at his rope and barking.

“Cephas, come sit by me and keep Rolfe quiet. Don’t see no one, but can’t take a chance someone might hear him.”

James approached. “Smell smoke. Maybe a campfire. I’ll go see. Won’t be gone long.”

“Did thou hear horses?” I asked.

“Nay, just smells like smoke over there in that haze. Probably nothing, always a haze in the woods.”

The feeling of suspense returned and my ear tuned in every noise. Branches crackled, chilly breezes ruffled leaves. The shade from the trees drew shadows that appeared more like men than branches. I thought I heard a whinny. I didn’t know which was worse—bandits or Claymore. Every once in a while I heard sounds from the box and told myself it was probably Toby easing a cramp. Worse for them. I wondered what they might be thinking. I looked at Cephas and thought how strange—Cephas and me free on the outside, and Toby and Sunshine, just like us, cramped in a box seeing nothing. We were the same age. Such a difference, yet I was as scared as they must be for what lay ahead.

I heard hooves. I turned and saw James returning from the rear. “Campfire, but nothing unusual. A man and his son dove hunting. We may hear their shots later.” He pointed to the bottom of the wagon, “How they doing?”

“Don’t know. They haven’t called.”

James rode to the side of the wagon and tapped twice with the hilt of his riding crop.

Two taps answered.

“Guess fine for now. Got four more miles of woods, and then thou will be clear the rest of the way.” James moved ahead, peering both ways through the trees. He pointed forward with his arms and cropped his horse into a gallop.

“Where’s he going?” I asked.

“To the edge of the woods, probably to check on the fields ahead,” Cephas responded.

“At least we’ll know the way across the fields is clear before he leaves us.” I tried to laugh, but my words came out scared. “Without James, it’ll be a long way home.”

“We’re over half way,” Cephas reminded me. “We’ll go faster once we’re out of the woods.”

An hour later, James returned bringing himself to a halt in front of the wagon. “Stop, we have to talk.”

“Up ahead is a two-pony trail leading off to the left. I think thee ought to take it.”

“Why? Did thou see horses?”

“Afraid so. Just before the clearing beyond the edge of the trees is an encampment of men, some mounted and others standing about. Not hunters, nor dressed like farmers. Could be bandits or slave hunters. I saw them soon enough to stop before they saw me.”

“What kind of horses? Any a big, dappled appaloosa?”

“Saw the rump of an appaloosa. How did thou know?”

“Rider wearing a gray coat?” I asked again.

“Aye. Exactly.”

“That’s Claymore.” My heart sank. Claymore could be an entire army for my chances of getting home. A trail off the beaten road was no better. I didn’t know the way.

“Where does the trail go, James? Hast thou ridden it before?”

“Don’t know the trail. I suppose if thou rides far enough, thou will end up at the Wabash.”

“The Wabash? That’s miles out of our way.”

“Can’t say it goes that far. Might loop around and come right back here. All I can tell thee is that ahead don’t look good. Even if it’s further, thou hast to take the trail.”

Rigid with fear, my mind froze. Cephas stared at me, his round eyes changing to fright.

James quickly reacted, his voice calm and reasoned. “Sarah Ann, can’t be too bad. Thou is over half way home. I have to turn back, thou heard me promise Pa I’d be home by dark.” James looked to the sun, “and that’s only a couple hours away. Thou knowst where Claymore is, far from where thou will go. Thou will be home safe before I get home.”

“What if we get lost?”

“Not that hard. Get down from the wagon and I’ll draw on the ground how to keep thy bearings so thou heads toward home.”

James drew a line in the dirt and marked it West. Then he added a perpendicular line and marked it North. Scratching a circle on the North line, he marked it Home. “After thou turns onto the trail, west will be straight ahead and north to thy right. When thou sees a chance, be sure to turn right, not left.”

“How will I know if the trail veers south instead?”

“If it’s headed to the Wabash it won’t. Have Cephas keep track of thy position with the sun. Thou shouldn’t be in the woods more than an hour, maybe not even that. The clearing beyond the trees stretched west as far as I could see. It’s the safest way to get around Claymore.”

I couldn’t keep my legs from shaking—Claymore was too close for me to feel anything but fear. I told myself again what James had said . . . I knew where Claymore was, and we hadn’t been seen. I turned onto the trail where only a single wagon’s wheels had passed since the last rain. I kept talking to myself. It would be foolish to return with James since we were less than ten miles from home. James had scared me mentioning the Wabash, but I knew we would reach Little Flint Creek before the Wabash. If the trail hadn’t turned north by then, we could follow the Little Flint even if we abandoned the wagon and went on foot the last few miles.

I thought I’d found my courage, but I hadn’t. I remained shaking all over—my hands cold, my forehead sweating.

“Sarah Ann, is thou afraid?” Cephas’s voice wavered. He only called me Sarah Ann when he was scared, really scared.

“Nay, silly. Of course not,” I lied. “Just keep an eye out on thy side of the wagon. Tell Toby to cushion Sunshine. Ride will be bumpy.”

I don’t know what I thought when James explained the trail. I realized now I was too scared of seeing Claymore to remember much. We weren’t on the new trail ten minutes when I knew it was nothing like he thought. The path twisted and turned first curving left and then right until we lost track of our direction. The canopy of barren trees was so thick we caught only glimpses of sun beams streaming between the trunks. Marshy rivulets crossed the trail and crows cawed from the trees. A single hawk from above shrilled. A large flap of wings startled me. Cephas hooted his owl call, and a wide-eyed owl with a rodent in his claws landed in the thick canopy above us, his white ruff adding texture to the barren trees. He cocked his head and screeched.

We advanced a little further; the tops of trees thinned giving us full sight of the sun. Cephas gave a triumphant yell, “We’re going west.”

Ahead I saw a fork in the trail with a chance to turn right—“Aye,” I told myself, “James said to turn right.”

I couldn’t judge distance in miles, only guessed at time. I sensed our progress had been slow and the afternoon had slipped by too quickly. The trail north appeared no different than the one we’d left, except the dropping sun shone through the sparser canopy. I kept my head bent and eyes on the trail.

Three miles? Five miles? Had to be closer than that. I didn’t see the trees thinning enough for the clearing James had described. Maybe the trail angled further south than I’d imagined. I began to worry we’d still be in the trees at dark.

“Can’t thou go faster?” Cephas asked, blinking back tears. “I - I want to get home.”

“Be patient,” I scolded.

As if I spoke too soon, around a curve the trail ended; the wagon faced a solid grove of trees. I pulled the traces and halted abruptly. The wood shifted on the bed of the wagon, Rolfe woke with a yelp, and I heard Sunshine cry from the bottom of the wagon.

“Sarah Ann, we’re lost.” Cephas panicked. “We’ll never get out of here.”

“Hush and listen,” I ordered.

I heard water rushing over rocks. The trees were taller and thicker to the right as if they’d sucked moisture from a creek. At a distance was a small clearing where men had rigged a camp to reach fishing holes. Maybe, we were near Little Flint Creek.

“Cephas, do you recognize where we are? Try to remember where Papa brought thee to hunt ducks the fall before he went to Ohio?”

Cephas brightened. “Doth thou think we’re at Little Flint? Does look like where we camped. Let me take Rolfe and see if I can find the creek.”

“Nay, stay here with Rolfe and make sure nothing happens to the wagon. I’ll go.” I trudged up a mound and in less than a quarter mile, I saw a creek. Had to be Little Flint. No other creek ran this far north.

When I got back to the wagon, the strong odor of a disturbed civet cat permeated the air sending Rolfe into a frenzy. Anyone within a mile would hear him. My eyes smarted. Cephas covered his nose. I yelled, “Shut him up and don’t let him loose.”

Cephas wrapped his arms around Rolfe’s neck holding him motionless. Rolfe struggled and then whimpered. Cephas stroked his back and scratched behind his ears. “Good boy, can’t have nobody hear us.”

I knew the wagon had gone as far as it could go, and I wasn’t about to backtrack to nowhere. “Cephas, remember when we were little, we played we crawled from the creek to our barn. Tonight, we will to do it for real. Get Toby and Sunshine out. We’ll follow the Little Flint until it meets Big Flint Creek at Brother Sleeper’s farm. Elder Isaiah’s there and can take Toby and Sunshine and shelter them.

I tied the mules to a tree near the water where they could reach grass to graze until tomorrow morning when someone returned for them. I took the leather straps which had connected the mules to the wagon, and at the bank of the creek, tethered myself first to Sunshine, then to Toby and then Cephas, last with Rolfe. “Quiet, don’t want to rouse farmers’ dogs. Make sure no one lets loose of the strap. We should get to Brother Sleeper before the moon comes up and gives us away.”

After we crawled through thorny brush, sunken cattails, and oozing bank mud for what seemed an hour, Rolfe barked and tore himself loose from Cephas dashing through the brush, his tail wagging his delight. He looped back and forth to make sure we followed.

Excited, Cephas called from the rear, “Rolfe knows the way home.”

“Keep him near so we don’t lose him.”

“Too late for his rope, but I know Rolfe. He won’t let us out of his sight. Not now.”

Ahead, a light flickered from a window. Soon two lights. A kitchen door opened. Rolfe barked and ran faster.

Another dog took up Rolfe’s call. A low voice came through the night air, “Is thou a friend?”

Cephas hooted his owl’s call.

A hoot of recognition answered back. “Sarah Ann?”

I hugged Cephas and squeezed Sunshine’s hand. “We’re safe. Thou will have a warm bed in Brother Sleeper’s barn.”

Buddell Sleeper met us. He was a stern man with a long graying beard, his thin lips pinched together hiding what everyone knew was a warm, hospitable heart. “Do ye want to stay the night?”

“Nay, only the shipment. ’Tis less than a mile and we’ll be home. Mother will be worried sick if we don’t get there tonight. Come on, Cephas, I’ll race thee.”

Cephas accepted my challenge, his boyhood confidence returning. “Thou can’t beat Rolfe and me.”

With Flint Creek to the left and dried corn stalks standing like sentries in the field to the right, Cephas and I ran, then stopped and caught our breath, and ran some more. We were euphoric, like carefree children playing “catch me” on a sunny day. We rounded the last curve in the road and saw the rising moon bringing a bright glow to the lane leading to our gate. Lanterns blazed in our windows. We were home!

We put on a burst of speed, and then halted abruptly in our tracks, mouths gaping with horror, feet frozen to the ground.

Tied to the gate was a large, gray appaloosa horse, a familiar saddlebag resting on its dappled rear flank.

Part 2

The Measure of Justin Claymore

The measure of a man, so said Burchfield Claymore to his sons was to know your place and be prepared to fight until your last breath to protect your rights. I believed Father although my own standing in the family hierarchy weighed heavily on my sense of justice. Never, Father declared, would a worthy Claymore be second to anybody: not in love, not in war, not in wealth. Where that left me in Father’s eyes as second son, I didn’t quite know, but it was obvious Father’s heart lay with his namesake, my older brother, Burchfield Claymore II.

Molded by Mother to be respectful and a gentleman, I was considered well-mannered and unassuming. I dared not remind Father that rather than establishing himself by the profitable utility of his own efforts, he, a Claymore fifth son, had arrived at his place of esteem by marrying well. Mother, nee Genevieve Stockwell, was the genteel daughter of a wealthy Savannah thoroughbred horse breeder. Even as a child, it grated on me when Father boasted that God graced him with good looks and fate graced him with Genevieve. I had watched my parents grow old together. Father looked every hour of his advancing age: his series of chins thicker around his neck and his demeanor more intolerant and cantankerous. My stately mother stood by her upper class notions, but to her credit, was more thoughtful and considerate.

Tonight, like all nights, the aging patriarch of the Claymore clan stood erect, his jaw jutting his authority much like a General inspecting troops to see that everyone was in his designated place. Seated to his right was Burchfield II and his wife Claire, a striking red-haired beauty, who relished their place of honor. To his left, me and my plain-featured wife Peggy with our fourteen-year-old son Hugh, and daughter Jenny, a girl of ten as pretty as her grandfather had been handsome. At the end of the long, candle-lit table, her chair flanked by a white-gloved household servant, a poised Genevieve, with salt and pepper hair shaped high on her head like a crown, waited for the venerable head of the family to formally seat her. The family was quiet, obeying Burchfield’s rule that no one speak until either he or Genevieve began the discourse.

“Why must we spend the summer stifling here in Lexington?” Genevieve fanned her face, then placed the perspiration-dampened napkin in her lap. “I much prefer Savannah. At least you could open the windows for the cool breeze coming off the Atlantic. I don’t ever remember our house being this unbearable.”

She turned and spoke to her waiting servant. “Now that we’re seated, Toby, you may begin service. The tureen first.” She announced to the family, “Ruby’s beef tenderloin in gravy tonight.”

“Of course, I remember Grandmother’s Savannah house,” Claire crooned. She often took on airs, purposely confusing others that she was a blood descendent instead of related by marriage. “Remember, Dahling, you took me there for the Breeders Ball. We had such a grand time dancing the night away.”

The elder Burchfield observed with some frequency, particularly after Claire did her carrying on, that his one disappointment was his eldest son had married below his station. I knew Father, like Burch, never missed ogling an over-endowed, beautiful woman, but to Claire’s discredit, the heritage she provided was colorless and without redeeming merit. Without a dollar to his name, her father, the progenitor of a large family, was a scratch owner of a small General Store outside of Lexington. Conversely, by my marrying the Baptist minister’s daughter, Peggy’s place in society, as well as giving him the only grandson in the family, I was saved from Father’s harsh criticism. For Burch, a male son, not his own was a cancer in his side for when the future required settlement of Father’s estate.

Claire continued, her sparrow-like voice tittering, “Well, I do declare, we should have demanded Ruby cook outside in the summer kitchen.” She twisted a large sparkling ring on her finger, patted the perspiration from her forehead, and dabbed her eyes with a lace handkerchief. She leaned over to Burch and kissed him on the cheek. “Dahling, why didn’t you insist? We’all could have been spared this awful heat.”

I winced, knowing the topic of weather was Claire’s favorite, the only topic in which I felt she was equipped to converse.

“Ladies, enough about the weather,” Burchfield snapped. “It’s August. What the goddamn else would you expect? Never saw such complaining.” He turned to his right, “Burch, I heard there was trouble in the fields this afternoon. Were you there?”

“Yes, sir, a small matter, really. Nothing worth discussing at the table.”

I laid my fork by my plate, my eyes narrowing to anger. “I would not consider the incident small. I got there in time to see Ike thrash one of the field hands with his riding crop.”

“Can’t believe Danny would be the one insolent,” Burchfield responded. “He’s been with me for as long as I remember. Independent for sure, but knows his place.”

Burch leaned toward Father. “No, not the old nigger. It was the wench, Sunshine. Ike said she was insolent, and when Ike says something, it’s the goddamn truth.”

“The goddamn truth, is it?” I persisted. “Ike don’t just oversee the hands, he hates them. I heard Danny say all she wanted was a dipper of water.”

“Ike decides who gets water,” Burch shot back. “The wench took liberties not hers to take. Got what she deserved.”

I painfully knew Father and Burch nearly always agreed; conversely Father and I seldom saw eye to eye except in our shared perniciousness. We both put the dollar on equal footing with one’s proper place. I knew what Father would say.

Burchfield nodded assent and slammed his fist on the table. “You damn right. Can’t have field hands slacking off. Tell Ike I said he did right.”

Genevieve blanched and turned to me, her voice low, resonating concern. “Where’s Sunshine now? She’s Toby’s sister, you know.”

I remembered I bought Toby for Mother, and Peggy had insisted on buying Sunshine because the wench had no other kin. I recalled even more clearly the other owners who bid up the ante against me. In the end, the two of them cost me fifteen hundred dollars. At the thought of the exorbitant sum, I fumed, my face turning an angry red. An overseer should know his actions would cause me considerable financial loss.

“I—I took her in,” Peggy admitted, her voice thin. “Saw no sense in a hand suffering outside.” She steadied herself and emphasized each word: “She was beaten about her head.”

Peggy paused. I suspected she felt Mother should register immediate concern, and Burchfield to insist we go immediately and attend to Sunshine. They did none of that, but Genevieve raised a questioning eyebrow as Peggy continued. “I wrapped her to stop the bleeding and put her on a cot in the little room behind the firewood.”

“Well, if it ain’t Benevolent Nurse Margaret at work,” Burch growled, his eyes shaded black by malice and brandy. He held an obvious dislike for his sister in law and refused to call her Peggy. In truth, he showed little admiration for me, accusing that I was a mama’s boy with a spineless, no-account drab wife. Peggy wasn’t pretty like Claire, and perhaps, I speculated, my brother found more aggravating the fact she was the mother of the only Claymore grandson.

Burch bellowed, “Make no mistake about it, that wench will be in the fields tomorrow, ain’t that right, Father?”

“Preposterous if she isn’t.” He glared at his daughter in law. “Don’t recall, do you, Genevieve, Peggy asking us permission to bring a wench inside? Ain’t her place.” Burchfield bushy brows stiffened. He blustered, “Move her immediately to the nigger quarters. Crops can’t wait for a field hand to quit whining. Burch, see to it she’s got a hoe in her hand at dawn.”

“But you can’t insist . . .” Peggy looked to me for support. “She’s hurt bad.”

“How bad?” I asked.

“She can’t see.”

*****

I realized Burch and Father had stopped listening and were deep in a discussion of their new thoroughbred mare and when its foal would arrive. Claire hung on to Burch’s every word finding frequent opportunities to nod and add “Dahling, I do declare, no one knows thoroughbreds better than you.”

With Peggy’s pronouncement that Sunshine was blind, Hugh and Jenny stared at each other, dropped their forks and stopped eating Ruby’s pecan pie. I simmered in anger; Peggy’s eyes pleaded to Genevieve who was watching Toby quietly disappear from the dining room.

Rising abruptly from the table, Genevieve took charge as she always did when someone or something—slave or family or horse—was injured. She beckoned Peggy aside and whispered, “Find Toby and take him to see his sister. I’ll keep them busy in the parlor.” Within hearing of the others gathering, she called her ruse to Peggy, “Go to the kitchen and tell Ruby to bring coffee.”

Noticing the absence of Toby, and Mother interceding on behalf of the wench Peggy had sheltered, I knew Sunshine would not be moved to outside quarters nor returned to the fields until Mother said so. I knew she believed that once purchased, the owner had the right to use his property any way he chose. But I also knew her one exception: never would she abide physical abuse for anything living. As a boy, to please her, I had taken lost turtles from the garden back to the creek for their safety.

I nodded approval to Peggy, and engaged father and Burch with brandy and talk of the coming spring stud schedule for their mares.

*****

Two weeks passed before dried scabs covered the cuts on Sunshine’s face, but with the swelling and deep bruises in her eyes, she appeared permanently blind. Peggy, with tears in her eyes, told me she was quite certain Sunshine would never see again.

Genevieve assigned Toby to tend to his sister the best he could, and when she went to lock the little room at night she often found the boy crying at the side of his sister’s cot. The Bible said to care for the “least of those,” and the two silhouettes against the fading light coming from a single candle flickering on the window sill were certainly the earth’s least.

A week later, during Wednesday evening supper, Burch sneered at Peggy, “When, Nurse Margaret, might we expect the wench in the fields? I think its time we stopped the horse play and let Ike get her hoeing cornstalks for fodder.”

“Peggy, don’t answer him,” Genevieve ordered. She turned to Burch with a sternness she found necessary more and more with her son, “I take great exception if you believe it’s your place to tell me what I should or should not do with Sunshine. If you don’t know a blind girl can’t hoe, then you don’t have the sense you were born with.”

“Now, Mother, how do you know she ain’t pretending?”

“I’ve already told you it’s not your place to argue.” Her voice left little room to misunderstand her intent. “I know these things.”

“Well if she can’t hoe, what can she do?” the elder Burchfield rasped, motioning to Toby to bring more brandy from the sideboard. “The wench has to earn her keep.”

“Sh-h-h. No more talk of this at the table. Toby can hear you.” She nodded to Father. “You and I will discuss Sunshine later.”

As if Mother had said nothing, Burch raised his voice loud enough to call the dead back to life. “Well if she can’t hoe, by god she has to do something.”

I felt the compunction to point out the obvious. “Ike should have thought of that before he beat her senseless. A blind wench won’t go for much if we try to sell her.”

Burchfield glared, “Damn waste. She ain’t worth nothing a’tall.”

“Seems to me she can slop hogs,” Burch snarled. “If she can’t do that, she might as well be dead. Just say the word, I’ll get Ike to finish what he should have done the first time.”

“That’s murder!” Peggy gasped. She stood, tugged Hugh and Jenny to follow, and bolted from the room.

I followed not far behind. “Burch, you fool. Shut your mouth.”

*****

I had never seen Father so upset. Genevieve tried to console him. “They must be here somewhere. Toby wouldn’t run off and Sunshine’s in no condition to go anywhere. You sure Burch looked everywhere?”

“More than everywhere,” Burch called from the doorway. “Under every damn rock. I tell you, Father, they’ve run away.”

“No one runs away from here and lives to tell about it. Someone knows something. By God, I’ll find out who.”

“But how could it have happened? I don’t understand,” Genevieve stuttered. “I locked the door behind Toby when he left Sunshine last night. I know I did. Justin, do you know how they could have gotten away?”

“No, I had gone to the barn before you closed down the kitchen. Never saw nor heard anything. Everything was locked up when I got back.”

“What about that wife of yours, brother? Bet she knows damn more than a little about them. God knows what her bleeding heart would do.”

“Burch, don’t you accuse anybody unless you know for sure what happened,” Genevieve scolded. “Last night, Claire was knitting and Peggy was stitching quilt blocks in the parlor. I followed both of them upstairs for the night after I shut down the kitchen. No one stirred, I would have heard them.”

I shook my head bewildered. It was well known Mother heard everything at night—even a cat’s paw on the stairway. “Father, what about the hands? Would any of them have helped Toby?”

“What are you insinuating about the hands?” Burch growled. “Ike don’t let any of them out at night. Not even to piss.”

“What you say is true, Burch, but I will talk to Danny personally. He’s been reliable for forty years. He’ll tell me the truth if there’s anything I should know.”

“Don’t go blaming Peggy.” I sent an accusing glare to Burch, “If they are gone, I’d say it had a lot to do with Ike beating Sunshine.”

“Nonsense. When we find them, Ike will see to it personally that Toby is in a heap of misery, worse off than the wench.”

“Burch, that’s enough.” Genevieve folded her arms, her body straight and rigid with anger. In spite of her love for her son, today she didn’t like him. “How many times do I have to tell you—Ike don’t oversee none of my house servants, never will. He’s not ever to touch Toby. Hear me? That’s my word.”

“Genevieve,” Burchfield demanded, “talk to Peggy and Claire and find out what they know. After I see Danny, I’ll decide who’s going after them.”

I responded to Father, “All well and good, but I ain’t standing by to watch my fifteen hundred dollars walk off our land.” I heard a rustle behind the parlor door that no one else seemed to notice. I saw a flying pigtail and the soles of scuffy shoes sneak back into the hallway.

*****

I found Peggy sorting socks from a basket of laundry, placing those with holes with her mending. I kissed her on her cheek and asked, “Where were Hugh and Jenny last night?”

“Why I suppose they were in their bedrooms. Why do you ask?”

“Toby and Sunshine ran away. We’re trying to figure out what happened.”

“If you believe Hugh or Jenny had any thing to do with them escaping, I think you’re wrong. Checked on them about ten o’clock and they were quiet.”

“Peggy, did you ever talk to them about Sunshine after she was hurt?”

“They were at the table. You know they heard everything before you shut Burch up. I tried to explain to them their Uncle Burch was letting off steam and wouldn’t think of allowing Ike to hurt Sunshine again, but they felt terrible about Sunshine.” Peggy paused, thinking aloud, “Doesn’t it seem strange to you they’ve spent a lot of time together since Sunshine was hurt? Maybe they are up to something.”

“Most unusual,” I agreed. “They usually fight.”

“Didn’t think much about it at the time, but I saw both of them with Danny yesterday afternoon. Figured he was telling his old stories.”

“They’re a little old for Danny’s stories, don’t you think? Same age as Toby and Sunshine, but I can’t believe they would help them runaway. They’ve been brought up better.”

“No, I’m certain it couldn’t have been them.”

I left to check on my horse in the event I would be the one father sent to hunt down the runaways. It was peculiar to everyone else, but not me, that my big, gray appaloosa was the only horse in the paddock that didn’t match the thoroughbreds. I secretly enjoyed the idea that like my horse, I didn’t match Burch nor Father. I gave my horse an extra bag of oats, brushed him down, and checked his hooves for burrs. Before I left the barn, I fetched his saddle and laid it across the stall’s back rail in readiness.

Questioning myself over a cup of coffee, my mind collected the facts as I knew them: Toby had visited his sister but had left. Mother was the last one to talk to Toby and actually see Sunshine in the little room. Claire and Peggy had gone upstairs. My thoughts made me laugh—wouldn’t have mattered where Claire was, she would be no help to anyone trying to escape. More to the truth, she probably did help by keeping Burch occupied in bed attempting to produce their own heir.

Peggy? My wife had a heart as big as the world, but would never be disloyal. If she helped them escape, she would have come and told me regardless of the consequences. She was like that. Our children, Jenny and Hugh? Had they been curious to hear the gossip when I saw them hiding outside the parlor or were they up to their necks in the escape?

Danny? In spite of Father’s loyalty, there was little that happened or would happen that he didn’t know about. But Danny, I reasoned, wouldn’t risk Ike catching him outside at night. Besides Ike’s guard dogs hadn’t barked.

It dawned on me. The solution to how it happened lay in finding how Sunshine escaped from the locked little room. Blind as she was, leaving was not something she could do by herself—someone else was involved. Mother had the key. I scratched my head, dismissing her from the suspects. I couldn’t believe she would have abetted trespassers, but felt compelled to ask. I found Mother arranging the last of summer’s purple and blue asters for the dining room table. “Mother, where was the key to the little room when you got up this morning?”

Without looking up, she answered, “Why on the hook above the stove, where it always is.”

-----

I wasn’t surprised I was the one winding my way north and west possibly as far as the Ohio River after Burch and Ike failed to turn up anything yesterday when they scoured the outlands, woods, and creek. Nor was I surprised Mother and Peggy seemed relieved I’d accepted without argument Father’s choice. I felt comfort that I could put their minds to rest.

Father thought of two possibilities that Toby might have chosen—either fleeing northeast to Cincinnati with the hope of connecting to the abolitionist movement guiding runaways to Philadelphia, or west from the Ohio into Indiana where Quakers were active with safe houses for runaways seeking freedom in Canada. Either way, someone had to have given Toby the information and coached him since he could neither read nor write nor was he privy to that kind of gossip. And for certain, he had no experience living off the land. When questioned, Danny claimed no knowledge of Toby’s plans insinuating no sweat-soaked field hand would likely aid a pampered houseboy. He did hint Ruby’s freed son lived east of Cincinnati.

I applied common sense to Toby’s circumstances and thought he more likely took off running with no specific plan. It would be like flipping a coin—they could be anywhere. With Toby and Sunshine on foot, I realized I’d trample through weeds and heavy brush, much like scaring up grouse or pheasants. My mind told me the runaways should be easy to find—couldn’t be far ahead. With luck, I might be home for supper.

For the time being, I planned to follow the meandering creeks, and stop and ask neighbors and plantation owners along the way if they had seen the pair. If I had been on any other mission, I would have enjoyed the bright Kentucky sun rising, orange streaked with gray like peeled citrus. The Elkhorn River and a small plantation lay ahead.

Entering the plantation, I recognized Father’s friend, Abe Jackson, at the gate squinting his eyes against the sun.

“Justin? That you, son?” Old Abe motioned for me to stop. “What brings you out this early? Hell, I ain’t got the cows milked yet.”

“We have two niggers missing—one a tall, skinny houseboy and the other a blind wench—a tiny thing about ten. Girl has a scarred face. You seen them?”

“When they go missing?” Abe asked leaning on a shovel, spitting to the ground, and swiping his hat across his overalls to kill flies swarming over a cat’s dead bird blocking the walk.

“Night before last. You heard of any one else having runaways or anyone hanging around getting niggers all worked up?”

“Haven’t heard or seen a thing. Don’t recall my dogs howling. You might check with Rob Simpson across the next hill. They’re closer to the river.”

I pulled on the reins, turning my appaloosa back to the road. I heard Abe call, “If I hear or see something, I’ll send word right away to your Daddy.”

At the Simpsons it was the same story. No noise, no sighting, no runaways.

My horse, picking his way along the bed of a creek, splashed hooves in the shallow water sending minnows scurrying in all directions. I frequently stopped and climbed bushy slopes checking for broken branches or footprints in the nearby woods. All the while, a singular question kept popping into my head: How had Toby and Sunshine managed?

When I peered at the sun at high noon and dug out my canteen with one of the lunches Ruby had fixed, I wondered if they had food. If they did, not only did someone help them escape, but the perpetrator had provided food and water. I couldn’t squelch the idea the traitor was one of us. When I’d last talked to Peggy, she reminded me people who are scared and desperate do things others wouldn’t even think about. I remembered Peggy’s hand on mine, pleading, “For their sake, I hope it’s you who finds them.”

A brisk breeze whipped up giving me a shudder. I reassured myself that I was doing the right thing. “Well for sure if I don’t find them alive, two starved niggers won’t make up for my fifteen hundred dollars.”

Nothing changed for three days. I found myself fighting to stay awake from the unbearable monotony of the unfruitful ride in the daytime and my lack of sleep at night. I wondered if Toby had chosen to hide during the day and run under the moon. Maybe I’d passed their hiding place and was ahead of them. I was about to reconsider backtracking when I saw smoke from a campfire ahead. Approaching, I saw two men, one making coffee over the flames of a campfire and the other skinning a rabbit. Their mottled appearance and the condition of their gear told me they had traveled for months.

They glanced up when I slowed my horse beside a cottonwood tree. I made sure my rifle lay handy across my saddle bag but noticed neither man seemed disturbed nor reached for his gun.

“Justin Claymore, Woodford County. Looking for runaways.”

“We aint from here, but will share our coffee with anyone who can tell us where the hell we are. Left Alabama a month ago looking for three ornery hands that took off with three mares from a plantation north of Athens. Traipsed clear through Tennessee but we don’t know where Kentucky started and where she ends. Been following the Big Star at night hoping to get as far as the Ohio River. Aim to collect a fair bounty if we ever catch up with them. Yours?”

“A houseboy of fourteen with his blind sister. Belong to me and my Father. I got ribs and grits to go with your rabbit and a little whiskey eye opener for the coffee. Mind if I settle a bit? Sure could use the company.”

“Say, if you are from around here, have you heard of a preacher fellow, Crucible Baal?”

“Yeh—hung around for a few months a year ago but he ain’t no preacher. We ran him off and thought he had the good sense to be gone for good. He knows if he comes back and stirs up our hands, my father will hang him.”

“Yesterday, a fella on down the road warned us to be on the lookout for a short stubby man, with a tall black hat, singing freedom songs, and carrying a Bible.”

“That’s him,” I confirmed.

“Fella said he lures runaways to follow him to freedom, but instead shackles them and takes them to an outlaw place outside Wheeling. He resells them off the auction blocks.”

“In my book, that’s worse than horse stealing,” the other man stormed. “We at least take them back to their rightful owner.”

“If we’re paid,” the first man laughed.

While the sunlight lingered, I drew on the ground a rough map of Kentucky and planted a pebble where they were at the moment. With a stick, I scratched in the creeks and rivers I knew about and the locations of several towns with large spreads where they could buy hay for their horses and supplies for themselves.

At my suggestion, we agreed to pool resources, spread ourselves out, and look for each other’s runaways.

Never learning to sleep well outside on rough ground, I lay awake in my bed roll propped up against my saddle. I let my mind recall Crucible Baal. An ugly man with a cut lip and black teeth, he was surprisingly well schooled with scriptures. I thought of Toby and Sunshine—would they have sense enough to see through his trap and run from him? A man with a Bible, promising freedom and offering food and a fast ride north, probably not. Particularly, with the burden of Sunshine not able to see.

I sat up in my bedroll. Time to flip a coin to either proceed or backtrack. If I retraced my steps and didn’t find their hiding place, not only would my money be a total loss, but the chances of Toby and Sunshine surviving Crucible Baal were thin. I knew what Peggy would say. I put my coin back into my pocket and leaned back on my saddle, my hat over my eyes.

My arrangement with the bounty hunters proved beneficial. They were men of moderation and good hunters. For the next several weeks, we spread out agreeing in two or three days to meet up again to share the information we had gathered. With each day with no live runaways in sight, it became more evident that old Crucible had gleaned the area clean. The dead ones . . . a different matter. More than once, I guided my horse away from a creek when a bloated body floated by or where thick brush entangled a maggot-ridden, naked slave. Repelled, I glanced into the brush just long enough to be sure the dark, emaciated bodies were not Toby or Sunshine.

With signs the Ohio River was not far off, we planned to meet in two days at a tavern in Limestone Crossing to determine whether to venture east or west. Although I was beginning to believe continuing would offer little possibility of finding my runaways, something gnawed in my stomach which kept me from turning back. Tired to the bone, at times, I thought I was losing my mind to still be hunting them, but on other occasions my hunt became a game, like a move on a chess board. Around each corner, or emerging from groves of trees, I played I check-mated my quarry and Toby and Sunshine would miraculously appear.

More dead than alive I was ready, I thought, rubbing my reddened eyes against the glare of the sun, to get stinking drunk at the tavern.

*****

The “Travelers Ale Parlor” was crowded, mostly with oarsmen guiding flatboats west on the Ohio to New Orleans, boys, barely men, herding hogs and steers east to Cincinnati, and a number of home-grown bums. I didn’t look much better; my elbows had come through holes in my sleeves weeks ago and my trousers not even fit for a nigger. Shortly, my two companions entered with a group of men who appeared they, too, hunted runaways. They seemed excited as if their lode of gold was near.

“What gives?” I asked.

“Just learned Crucible Baal was set upon by a posse of planters and taken by force to a magistrate in Cincinnati. ’Tis like we feared, he had with him near forty runaways who scattered like fleas when the posse approached. Several have been picked up, but most are loose in the area. With luck, we’ll finally get our runaways.”

“Grab your things, Claymore, and your horse—ain’t got time to stop and chaw.” “Head west—with the posse none will flee east.” One of the men motioned to the other, “Check for rafts. There’ll be as many floating as walking.” His eyes glistened with anticipation. “Shouldn’t be long, now.”

Following the Ohio River with its water mud brown and its multitude of bordering sycamore trees, I came upon runaways chained to each other and dragged by hunters back through the woods. From Crucible’s treatment, the runaways were much the worse for wear and did not offer resistance. I suspected some might welcome being captured to return home. In the thickened forest, I thought one tall skinny one might be Toby, but when I looked twice, the boy’s features were different. After ten miles of no success, I reconnoitered with the other two hunters.

“Zero. No damned luck,” one companion muttered to his partner. “How about you?”

“Searched rafts and followed the shoreline, none ours.”

“Seen a bunch picked up, but not any ours,” I reported, disheartened and doubtful. “Maybe, old Crucible didn’t capture ours after all.”

“He had them all right. They’re either dead or somehow escaped. Men at the tavern told me Clinton is two days ahead on the Ohio side and is thick with Quakers. I suggest we go at least that far and see what we can muster out of their safe houses.”

Slumped over the pummel of my saddle, I was a man, like a skeleton riding a horse, and too tired to offer any other suggestion. I imagined Peggy’s warm embrace, and then Father’s uncompromising face flashed in front of me. I roused myself, jerked the reins, and fell in line.

Clinton was indeed a Quaker’s heaven. Wagons loaded with cut wood were coming and going on the dirt-packed road. From the fragrance penetrating the breeze, someone had been cutting hay somewhere.

On one farm, everyone —men, women and children—were busy: a man plowing under a field of clover, an old man building a log hog shed, girls in white sun bonnets harvesting garden crops, and boys with black hats loading wagons with chopped wood. One woman, with a heavy oak branch, energetically whipped a quilt hanging on a clothes line. The quilt, like others I’d seen hanging on fences at other farms, was appliquéd with a log cabin with smoke coming from its chimney.

I worried the appearance of three horsemen coming down their road might alarm them. With some semblance of a gentleman, I appointed myself to ride ahead and motioned for the other two to stay hidden in the woods. I knew that although Quakers wouldn’t be armed, they might stare mutely, and go on with their work.

With his shirt sleeves rolled to his elbow, the man plowing the clover field near the road did look up.

“Justin Claymore of Woodson County, Kentucky.”

“Mordecai Ellis.” The farmer added dryly, disinterest covering his face, “Far piece from home. Are thee a friend?”

I couldn’t say yes I was a friend when I obviously wasn’t, or no giving Mordecai the satisfaction I was an outsider. I nodded respectfully. “Looking for two children who escaped from a scoundrel who kidnapped them. Sent by my mother to bring them home. She’s worried they might be lost or hurt.”

From the bustle in the farm yard, I had the feeling I had interrupted something. The girls in the garden raced to the house. Immediately, the young woman beating the quilt ran. Soon heavy curtains covered the windows.

Mordecai responded coldly. “You scared our women. They aren’t used to strangers. Thy best be making thy way. We’ve seen no lost children.”

Wanting to examine further the possibility of a safe house, I eyed hay stacked outside Mordecai’s barn. I reached in my pocket for coin. “Could you spare some hay for my horse. Ran out of feed yesterday.”

The farmer called to a lad, a miniature Mordecai, looking on from the fence. “Hiram, bring a pitchfork of hay and a bucket of oats.”

“No need for the boy to fetch it—I can ride over to the barn.”

Disregarding my ploy, Mordecai motioned for Hiram to hurry. He turned to me. “Put thy coin back in thy pocket. We can spare a fork of hay and oats.”

I began to say thank you when Mordecai pulled the plow’s strap around his shoulders, gripped the handles, and dug into the soil leaving me with my words half-spoken.

The boy arrived with hay and placed a fork of hay and a bucket of oats in front of my horse. He pulled a stick and whittling knife from his pocket and climbed back on the fence and stared.

Blood rose in my head. I was furious. Thwarted by a boy, with a cocked black hat, sitting on the fence whittling a birch stick to a sharp point for hunting rabbits was humiliating. I stood helpless unable to advance my cause. I watched my gray, dappled appaloosa feast.

*****

This time, I demanded we go ahead to the Wabash River when my two companions thought success unlikely. “It don’t feel right. Those rubes back there are getting ready for something. There’s too many of Crucible’s runaways unaccounted for.”

My companions had already turned their horses to continue west. I followed.

At noon, I turned north and the other two forded the river to search the western side of the Wabash. At Vincinnes, we joined on the eastern side of the river and headed into a heavy interior woods where we encountered a girl and her brother driving an apple cart being attacked by two bandits. We hooted and they ran. Remembering Hugh and Jenny, I decided to send my companions forward, while I saw a girl and her brother to safety at Crawfordville. My companions and I met again near a field at the far edge of the woods not far from what I thought was Little Flint creek. We joined another group of bounty hunters anxious to share runaway information, and decided to camp with them for the night. Before I dismounted, I knew I was too exhausted to sleep on the open ground. Beset by three months of hard living, I’d gotten nowhere. My eyes ached from staying open. I obsessed the thought of a real bed in a house with four walls and an open window.

Confirming my companions would start north in the morning, I told them, “I’m riding ahead tonight.” Sarcasm entered my voice. “Intend to rent me a room in one of these fine Quaker houses whether they invite me in or not.”

One of the men pointing to a creek confirmed, “That’s Little Flint—might find someone north from there who will take you in.”

“Thanks.” I tipped my hat and rode on.

It was later than I wanted, almost dark. Ahead two lanterns flashed in a window. I remembered my experience with Mordecai Ellis and wasn’t in the mood for more abuse from a Quaker, but my bones told me it was time to stop.

I tied my horse to the gate—everything was quiet, no dog barking. I ran my hands through my hair and straightened myself up. I knocked on the door.

A large woman, obviously nearing the time for birthing, answered, “Did thee knock?”

“Ma’am, I know I’m highly irregular in asking, but would you rent me a room for the night? Been on the road a long time without a good night’s sleep. Won’t cause you no trouble.”

I heard a gruff voice booming behind the woman, “Rachel, who is thou talking to? Have thou lost thy good sense? Come away from the door.”

“Just a minute, Henry, the man wants a room.” She closed the door behind her and stepped onto the porch so as not to be heard. She asked quietly, “Who are thee and where did thou come from?”

“Justin Claymore of Woodford County, Kentucky. My little sister and brother were kidnapped and my mother sent me to find them. Was in Crawfordville yesterday. Saved a young woman and her brother driving an apple wagon near the Little Flint from bandits. They were so much like my sister and brother . . . I couldn’t leave them alone in the woods.” I paused, hoping I had aroused a mother’s sympathy. “Rode with them till I could leave them safe at a meetinghouse. I’m alone and promise I mean no harm.”

The woman blanched, then quickly extended her hand. “Justin Claymore, is it? We do have a spare room—nothing fancy, but good enough for a night’s sleep. Washed up the bedding yesterday.”

Little did I know that long into the night, when all was quiet except for my snoring and Rachel’s beating heart, a mule and a wagon piled with chopped wood, driven by Buddell Sleeper, rolled silently along the road, heading north.

Part 3

TOBY and CEPHAS

A Negro man, old by life’s trials and tribulations, rested on a bale of hay watching a thin, bearded, sun-browned man in overalls tie his horse to a stall in the livery stable, its plank siding chipped and weathered gray by time and wear. “CEPHAS A. ELLIS, LIVERY, PILGER, NEBRASKA” was etched in large letters on the front. Wagons and buggies, their horses removed to the stable, provided shade for hay bales placed in a square for town folks who often came to sit a spell and talk.

Ellis Livery Barn, Pilger, Nebraska

It was a stroke of luck, or they both would agree later, the Lord’s doing, for the lone Negro to be passing through the little country town which boasted exclusively Swede, German, and Welsh inhabitants. It was the Negro who recognized the name on the faded green sign and approached the owner asking to board his horse.

They clasped each other’s hands, moisture formed in their eyes at their remarkable recognition. Soon they were beyond the shock of knowing each other. No one, in his right mind, would guess the two had shared a moment in time or would ever meet to exchange their stories. Toby speaks.

*****

Wipin teary feelins from my runny eyes, I started my tellin. “It’s not hard to ’member. In forty-five years, I reckon I done cried twice. First time was when I was ’leven, I see’d dis man, his fat belly dropping almost to his knees, in a straw hat, white see-sucker suit, his vest poppin open, and a black ribbon tie chokin him at his chin. He pull my mother from da auction block and shove her into a waitin cart with his shackled slaves. I could do nothing fer her—my sistah and me were chained together next in line waitin to be looked at by a handful of men and one woman. My mother’s voice still rings hard in my head: ‘Toby-boy, Toby-boy, yo take good care of yo sistah.’ When Sunshine clutched me screamin fer her mother, her sobs was my sobs.”

“Auctioneer summoned me, but I couldn’t leave Sunshine alone. His deputy tried to separate us, but I grabbed her firm-like when she forced herself limp refusin to let go of me. I seen a woman in a brown hat and dark church dress ’mid da gatherin tug her man’s elbow and whisper somethin. After dat, her man called to da auctioneer, ‘Bring them both.’ Dat is how Sunshine and me became property of Burchfield Claymore, gentl’man, horse breeder, and planter of Savannah, Georgia. And dat ’plains why Sunshine and me never seen mother again.”

Cephas pulled his bale closer so as to not miss my words. My voice cracked as it always did when I speak of my heart-broken mother. Ev’n with Cephas so near, I struggled hard to keep my talkin from slippin back into quiet memory of dat woman.

“Claymore’s? Somes were good, somes was bad. Mistress and her son’s woman, Miss Peggy, were good ones as long as you hopped to whatever dey wanted. Massa and his son, Mistah Burch, were mean. Miss Claire was Mistah Burch’s woman and she accused Sunshine of stealin her ruby brooch. Sunshine never took nothin from Miss Claire, but Mistah Burch believed otherwise and forced Sunshine from da house and put her in da fields hoein corn. Overseer was Mistah Ike, and if you believe Massa and Mistah Burch were mean, Mistah Ike was da debil hisself. When others weren’t lookin, he’d take lil girls behind bushes, and I guess most people knowed what dat mean.